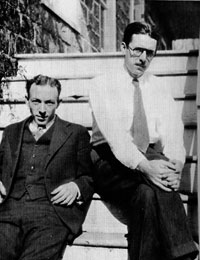

E.B. White (left) and James Thurber, in 1929.

Is Sex Necessary? James Thurber and E.B. White Weigh In With 'High Spirits'

Perhaps no topic has been more written about, theorized, or worked over, so to speak, than sex, especially as it relates to a couple’s psychological compatibility. Lest we think advice on sex, love, and marriage through the lens of psychology is a relatively recent phenomenon, however, a flood of such material for the general reader was already filling bookshelves by the 1920s. Donald Freedheim, in the Handbook of Psychology (1), describes the 20s as "the decade of popular Psychology."

Among the more astute observers of this trend were authors James Thurber and E. B. White. In the 1920s they shared an office as staff writers at The New Yorker and in 1929 they joined forces to pen Is Sex Necessary?, a gently hilarious spoof of texts which claimed to diagnose both sexes' innate psychological tendencies and identify a raft of elaborate "complexes," all to the betterment of the modern relationship.

And just what were young couples in the 1920s up against? What pop psychology nuggets of wisdom were Thurber and White targeting?

William J. Robinson, who authored Sex Knowledge for Men (1920), asserted in no uncertain terms that a successful conjugal experience lies at the heart of a young bride’s very mental stability because, as experts knew, "a healthy vita sexualis is the remedy for many troubles of the brain." In fact, Robinson declared, "The anabolic energy of woman may be said to desire avidly the catabolic force of man as the completion of being. No argument, no evasion, can destroy this fact of human life."

Experts also proposed "scientific" tests to determine a couple's compatibility, such as the "nervous disorder" test published in the April 1924 issue of Science and Invention by Hugo Gernsback. This called for a gun to be fired into the air unannounced, so the reaction of the male and female could be duly measured. Too intense a reaction from both apparently did not bode well for the union, scientifically speaking.

In short, couples were supposed to acknowledge the primal and essential nature of sex, but simultaneously do their best to control it. Walter Gallichan, in The Psychology of Marriage (1918), did his level best to steel young couples to the swirling maelstrom that is the human psyche:

Good God.

Out of this psycho-quagmire sprang the inspiration for Thurber and White's comic relief. White,

recounting in 1950 his and Thurber's approach to the task at hand, said:

Is Sex Necessary?, devoting its pages specifically to the American species of male and female, quickly loads up with faux psychology jargon—which, incidentally, gives birth to a delightful Glossary—and acknowledges a debt to two fictional psychologists, the "deans of American sex," Drs. Walter Tithridge and Karl Zaner.

The book gets right down to business in its Preface, describing the troubling prenuptial rituals of the modern bride-to-be, albeit in a slightly less terrifying manner than, say, Walter Gallichan's:

However, the next Q.T. that I encountered I placed under observation more gradually. I used to see her riding on a Fifth Avenue bus, always at a certain hour. I took to riding on this bus also, and discreetly managed to sit next [to] her on several occasions. She eventually noticed that I appeared to be cultivating her and eyed me quite candidly, with a look I could not at once decipher. I could now, but at that time I couldn't. I resolved to put the matter to her quite frankly, to tell her, in fine, that I was studying her type and that I wished to place her under closer observation. Therefore, one evening, I doffed my hat and began.

"Madam" I said, "I would greatly appreciate making a leisurely examination of you, at your convenience." She struck me with the palm of her open hand, got up from her seat, and descended at the next even-numbered street—Thirty-sixth, I believe it was.

Also, as promised, Thurber and White do take "a quick look at love and passion" by attempting to distinguish one feeling from the other. Perhaps it is for the best that few of us write actual letters these days, as we learn it is during such an activity that "the question of deciding whether a feeling be love or passion" may assert itself and cause some serious vexation:

After "a brief estimate of the comparative beauty of Anne and the girl in the scarf, with the girl in the scarf coming out a half length ahead," there follows a testy dialogue with the self about beauty not being everything:

"Oh, there's quality of mind, and community of interest, and chemical attraction (chemical attraction is a term you've picked up recently from reading books on sex and life). When I get right down to it, if I were to meet that girl in the scarf, I probably wouldn't like her."

"No, but you want to meet her all the samey, don't you?"

"Well . . . I mean . . . a man can't; I mean . . ."

"Yah, you know you want to meet her!"

"Aw, shut up!"

Thankfully, email is so much less fraught.

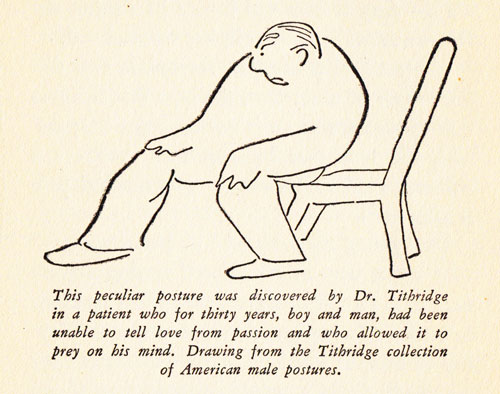

Saving some of the best for last, any discussion of Is Sex Necessary? would be incomplete without mentioning its 52 illustrations. They are the unmistakable handiwork of James Thurber, who today may be as well known for his unpolished cartoons of people and animals as he is for his writings. Thurber himself alluded to this in a 1939 Los Angeles Times article:

One day White took a thin manuscript to Harper and Sons with the electrifying title, "Is Sex Necessary?" Recognizing a vital question when they saw one, Harper’s were all for publishing. But White made one condition. They must use the illustrations by one James Thurber.

"They looked at them," said Thurber, "then, making a great effort at politeness, they said: 'These are—er—the artist’s rough ideas for the illustrations?'"

White assured Harper’s that these were the finished jobs.

The book came out and the screwy drawings made a hit.

"You see," said Thurber sadly, "that’s the way life goes. I write stories with the utmost care, rewriting every one from three to 10 times. I have written so many of them for the New Yorker that six volumes of prose have already been published in book form to only one of drawings. Yet they say, 'Thurber? The bird who draws?'" (4)

Among the Thurber fish, dogs, confused men and women, and one lion found in the pages of Is Sex Necessary? there is also, splendidly, a Thurber map, with the accompanying caption:

P.S. If you haven't laughed until you've cried recently, please turn to the discussion of guest

towels in Chapter VII ("Claustrophobia, or What Every Young Wife Should Know"), or to the

rhapsodizing of the "mollusc" in "Answers to Hard Questions." A box of tissues is mandatory.

![]()

2. Walter M. Gallichan, The Psychology of Marriage (1918) Chapter 1, "The Supreme Impulse," pp. 9-10.

3. E.B. White, Introduction to 21st anniversary edition of Is Sex Necessary? (1950).

4. Thomas Fensch, Conversations with James Thurber (1989), Thurber's interview with Arthur Millier from The Los Angeles Times Sunday Magazine, July 2, 1939.